The history of contraception access in Ireland

Dr. Caroline West is a consent educator, the host of the Glow West podcast, the sex and relationship expert for Bumble Ireland and a relationship advice columnist for the Irish Independent. She holds a PhD and MA in Sexuality Studies from Dublin City University. In her latest role, she’s teamed up with morning after pill brand ellaOne, as part of their #ShareTheFacts campaign, to share her wisdom on sex, contraception and consent culture in Ireland.

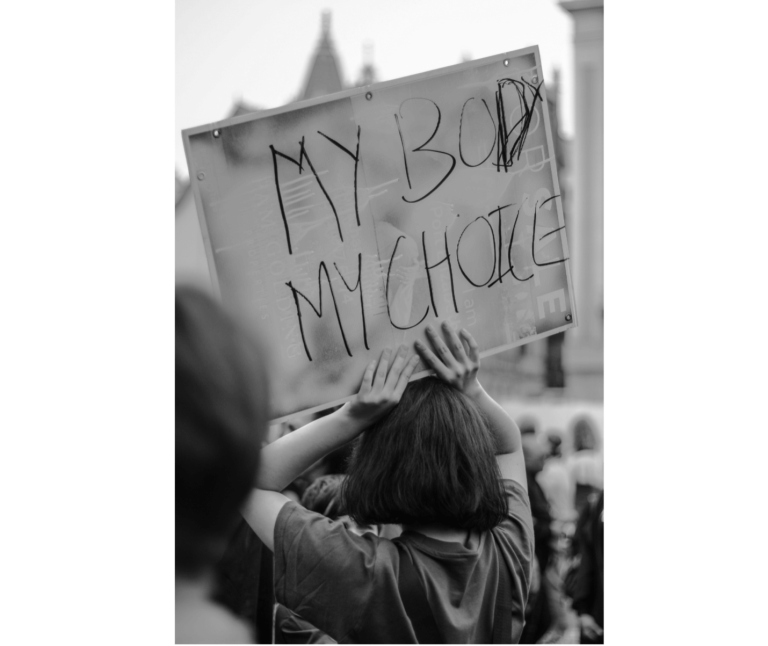

Caroline is passionate about creating spaces for calm, informed conversations about sex, and works to reduce shame and stigma around sex in Ireland. In the first of her monthly blog posts, she charts the long journey Irish women have been making to achieve bodily autonomy:

While we celebrate the news that contraception is now free for people aged 17-25, such a positive step forward in family planning was not always welcome in Ireland. There is a long history of having to fight for reproductive rights and access to contraception, and despite welcome steps forward, there are still gaps to fill in.

Ireland’s longstanding contraceptive ban

Contraceptive was made illegal in Ireland in 1935 under Section 17 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1935. This act made it illegal to sell or advertise contraceptive goods, and contraceptives were now to be considered prohibited goods. This stance on contraception was cemented further with the Censorship of Publications Act 1946, which banned books about family planning or contraceptives. This silence, combined with no sex education in schools, meant that many people struggled to understand the reproductive cycle, and often had no idea what pregnancy entailed.

While many countries in the Western world celebrated access to the contraceptive pill in the 1960’s and 1970’s, Ireland did not share in this sexual revolution. San Francisco notoriously enjoyed a summer of love; Ireland had many winters of discontent for women trying to manage their family planning options. However, while the pill was technically illegal in Ireland, it was prescribed by many doctors for regulation of periods, and this loophole allowed people to plan their families. This plan had to involve a doctor who was sympathetic and understood the reality of prescribing contraceptives, and younger people or those with smaller families were often not able to access the pill this way.

People often felt conflicted when planning their families, as they essentially had to make a choice between their religion and contraception. The Catholic Church had a long-standing heavy influence in Ireland and advocated for large families. The church was strongly opposed to methods of contraception such as the pill or condoms, although they did permit ‘natural family planning’, such as the rhythm method. This method can often have a high failure rate, relying on the man to pull out before ejaculation, or for the woman to monitor the viscosity of her vaginal mucus alongside her menstrual cycle.

McGee milestone

In 1974 things shifted enormously when the McGee case reached the supreme court. Mary McGee was a married woman with four children who had been informed that future pregnancies would endanger her health. She was advised by her doctor that contraception would be the right course of action, but due to Irish laws she had to import this product. However, the contraceptive jelly that she ordered was stopped by customs. Taking legal action, she argued in court that her right to privacy was breached, and the Supreme Court eventually agreed with her that she had a right to privacy when it came to her family.

The 80’s abortion law

Abortion was outlawed in 1983 when the state passed a law that equated the life of the fetus to that of the mother, and in 1986 the High Court argued that access to information on travelling outside the state for abortion was illegal. Grassroots activists fought these laws, and when shocking cases such as the 14-year-old rape victim in the 1992 X case was refused access to an abortion, abortion became a heated discussion in feminist, medical, and religious circles.

The 1970’s-1990s also saw societal changes in relation to condoms. Before 1991, condoms could only be sold to those over 18; this was lowered to 16 with a new law in 1991. Feminist group Irish Women’s Liberation Movement travelled to Belfast by train to buy contraceptives as a protest against the law banning condoms. This became known as the condom train, and as the women arrived back in Dublin they were greeted by both Gardai and supportive crowds as they waved condoms and pill packets in the air triumphantly.

Breaking the law to break down the barriers

In 1978, activities from feminist groups set up Dublin’s first contraceptive shop called ‘Contraceptives Unlimited’, which broke the law by selling condoms. The aim was to raise awareness of the demand for contraception and how the law was unfit for modern Irish society. However, condoms were still restricted to being sold to over 18s in pharmacies, family planning clinics and other health outlets. This came to a head in May 1990. The Virgin Megastore, based on the quays in Dublin, were fined for selling condoms over the counter. These were sold on behalf of the Irish Family Planning clinic and were a way for young people to access contraception without going to a GP. They were fined £400, which was increased to £500 in court and rock band U2 paid the fine. This became a catalyst for change and condoms became legal for over 16-year-olds in 1991.

Today’s remaining contraceptive barriers

Fast forward to today, and while various contraceptives can be found in chemists, sex shops and by prescription, there are still some barriers in place. Cost was prohibitive for many, as some long-acting contraceptives such as the implant could cost hundreds of euros. Many people found the lockdowns in the Covid pandemic a challenge for managing their sexual health, as doctors’ surgeries were overwhelmed and STI clinics closed. To combat this, the Cork Sexual Health Centre send out packages of lube and condoms via post to those who requested them.

With regards to abortion, this was legalised in 2018, although this law has not been as inclusive as many activists hoped. A three-day waiting period requiring two GP visits is inaccessible for some, and the cut off time means that many people who later receive a diagnosis of a fatal fetal abnormality find themselves forced to travel abroad for an abortion. Those who are disabled, asylum seekers, or economically disadvantaged can struggle to use this option.

Modern and inclusive sex education that includes contraception, including the morning after pill, and increased access for all will allow people to be empowered to control their own fertility, sexual health, and make informed choices about family planning. We are a long way from the laws of the 1930’s, but there is still much progress to be made.